Using virtual reality to support addiction recovery in West Northamptonshire

For our first Digital Northants Story of 2026, we spoke to Dr Mu Mu, Professor of Human-Centred Data Intelligence at the University of Northampton, and Masum Ahmed, Commissioning Support Officer at West Northamptonshire Council, about a new partnership with local addiction support services to explore how virtual reality (VR) could help people on their recovery journey.

Funded through Innovate UK, this short pilot project aims to translate university research into practical, real-world support that benefits the community.

Innovate UK funding is designed to support knowledge transfer partnerships, bringing together universities and business or public sector partners, including local authorities. The goal is to use research and innovation developed in universities and apply it in ways that deliver tangible social impact. In this case, the focus is mental health support for people experiencing addiction recovery.

Dr Mu Mu, from the University of Northampton, explains that the project builds on years of VR mental health research already underway at the university.

“We saw an opportunity to partner with West Northamptonshire Council to deliver a VR mental health intervention to help people through the challenging journey of addiction recovery,” he says.

“Recovery is hard. It’s full of setbacks, vulnerability and stress, and it requires people to actively engage with therapies such as dialectical behavioural therapy, or DBT.”

DBT and similar approaches focus on skills like mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance and self-compassion.

While many service users are introduced to these ideas, the challenge often lies in practising them, especially during moments of stress. Through research and conversations with local charities, including visits to addiction service providers, the team identified a clear gap.

“People are aware of these effective therapies, but the gap is practice,” Dr Mu explains. “A lot of members don’t feel confident actively engaging in those coping skills when things become stressful. There is learning and support already there, but people need help to practise those skills in a safe way.”

That gap is where VR comes in. The team is developing a VR intervention called Inner Voice, designed to provide a simulated environment where people can practise coping skills without judgement. Clinically, this approach is often described as graded exposure: safely exposing people to situations that may trigger difficult emotions, while giving them tools to respond differently.

“In this environment, people can identify emotions, practise self-compassion and develop life-changing coping skills in a private, safe space,” says Dr Mu. “They’re not being judged, and they can repeat the experience as many times as they need.”

The Innovate UK funding supports a three-month sprint project, allowing the team to move quickly from concept to prototype. A full-time research associate, Ben Wells, has been employed to develop the VR experience, supported by games artist Andy Debus and a wider academic team specialising in game design and programming. Wells is a graduate of the university’s own games programme and is now working as a graduate game developer on the project.

Crucially, service users and frontline providers are involved throughout the development process. “We’re designing with people rather than just for them,” says Dr Mu. “The visits to our partners were about understanding needs and requirements, then building a prototype and going back to validate whether what we’ve built actually matches those needs.”

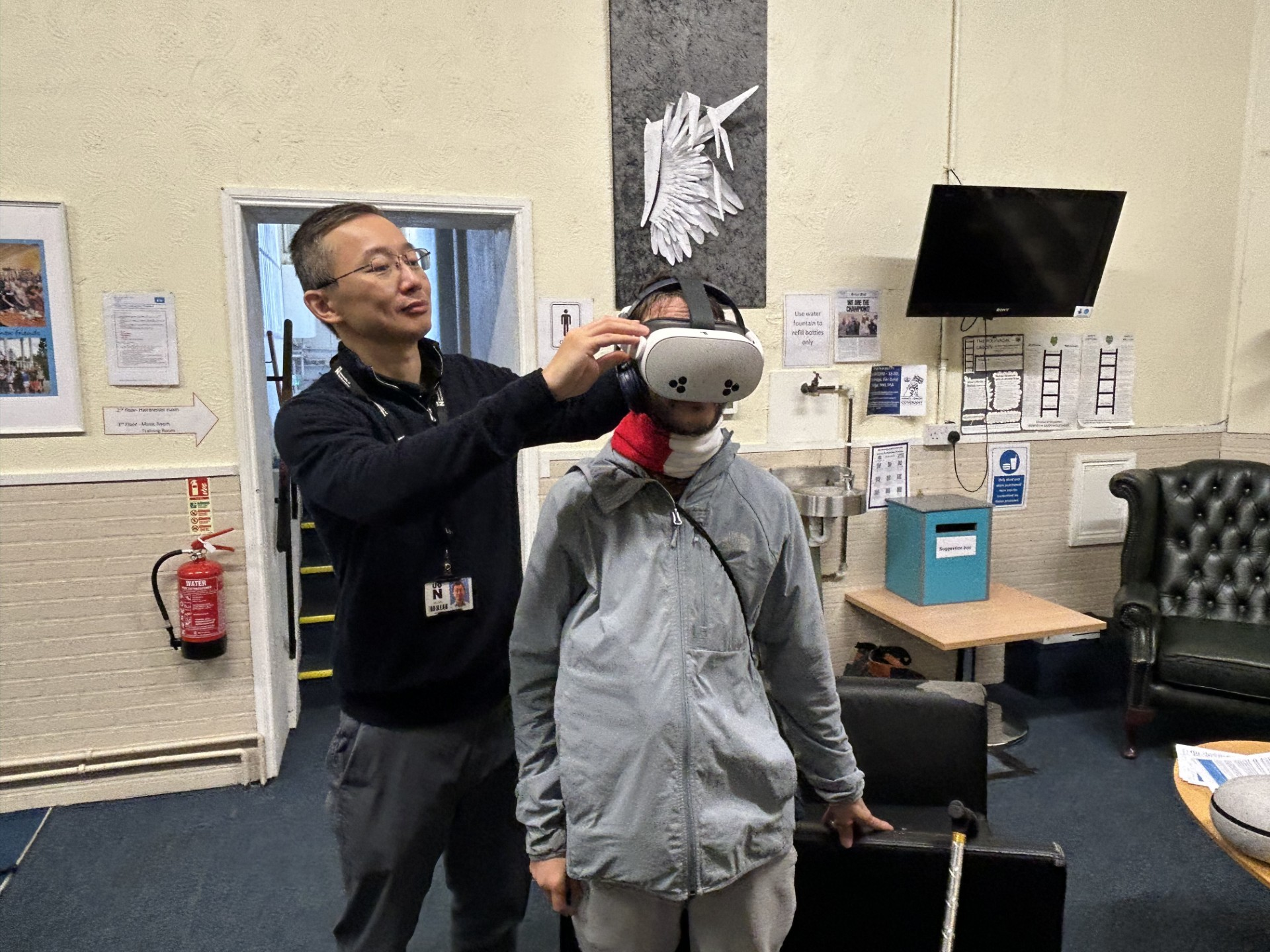

Because VR is unfamiliar to many people, the team uses a rapid, iterative approach. Rather than asking service users to imagine what might work, they create something tangible that people can see, feel and respond to. Feedback then shapes the next iteration.

Masum Ahmed from West Northamptonshire Council describes the council’s role as fostering partnerships and ensuring equitable coverage across the county: “As we begin to plan the launch of the new substance misuse service, we want to learn from pilots like this to better understand how digital tools can support future delivery. Virtual reality is one example of a new approach that could influence our views on engagement, accessibility, and innovation in the long run. It won’t replace the value of in-person support.”

Early feedback from our partners has been extremely positive. When the team brought an existing VR anxiety-management app to the service, there was strong interest from both service users and staff.

“There was a long queue to try it,” says Dr Mu. “People reported feeling tense before the session and completely relaxed afterwards.”

The app, which features calming underwater environments such as swimming with dolphins, has already been piloted in SEND schools and is being considered for wider use through family hubs and community services.

The team plans to return to our partners to gather more structured feedback through questionnaires completed before and after sessions, alongside observations from support workers.

Success, the team explains, can be measured in different ways. In the short term, self-reported changes in anxiety, emotional regulation and confidence offer valuable insight. In the longer term, the more complex Inner Voice simulation would ideally be evaluated through clinical studies, potentially involving NHS partners and clinical psychologists, to assess its effectiveness in addiction recovery.

“There are really two strands,” Dr Mu says. “One is low-level anxiety management that can help the community now. The other is building a more clinically focused therapy for recovery, involving exposure and skills practice.”

An important aim of the project is inclusivity. The team is keen to hear from people who may not typically come forward for support, including those with co-occurring conditions. Masum highlights that many people in substance misuse services also experience mental health challenges, creating a cycle that can undermine recovery.

“Traditionally, treatment has focused on addiction alone,” he says. “But unless you deal with the mental health side as well, you won’t see as much success. This pilot has the potential to engage that population in a different way.”

The use of game design principles is a key innovation. Rather than feeling like therapy, the VR experience feels playful and engaging. “People don’t feel like they’re doing clinical exercises,” Dr Mu explains. “They feel like they’re playing a game or relaxing in an environment. That makes it more accessible, especially for young people.”

With encouraging early feedback and interest from commissioners and providers, the team hopes this pilot will be the foundation for wider collaboration, further funding and expanded community impact. Dr Mu's closing message sums up the Digital Northants ethos: “We want whatever we build to benefit as many people as possible, across different backgrounds and needs.”